In the early 1960s, 19-year-old Bob Dylan arrives in New York with his guitar and revolutionary talent, destined to change the course of American music. Forming his most intimate relationships during his rise to fame, he grows restless with the folk movement, making a controversial choice that reverberates worldwide.

Bringing Dylan’s specific story to the big screen for all to uncover his unique enigma of a personality, James Mangold has crafted A Complete Unknown, with Timothée Chalamet delivering career-finest work as the mysterious musician.

As the film arrives in Australian theatres this week, Peter Gray spoke with the lead creatives of the film, including director Mangold and Academy Award nominated actor Edward Norton, who portrays legendary American folk singer-songwriter and activist Pete Seeger, one of the most influential musicians on Dylan during the film’s specific period of his career.

Here, the two discuss navigating their respective roles and how it was to work opposite Chalamet in such a committed role.

Edward, I feel like Pete Seeger was remembered as this unwavering purist. Were there any lesser known aspects of his personality that you found surprising or compelling when researching him?

Edward Norton: Yeah, many. I think anytime you dig into the public, or the interpersonal dynamics that are behind a public persona, you hear stories and learn things, and, you know, there’ll be funny things in the process of rehearsing something, like there’s a couple of moments where Seeger and Dylan haven’t seen each other in a while. And Timmy and I were rehearsing things, and you’re trying to figure out the dynamics of the scene, and I remember that fundamental question came up for both of us, which is “Are these people who would embrace each other if they haven’t seen each other?” I was talking to Joan Baez about Pete, and she was just a treasure trove of memories and details, and really honest recollections of him. I asked her, “If you hadn’t seen Pete in a while, would you give him a hug?” And she went, “Oh my God, no!” She said how they were both such hippies and he was such a Calvinist. He used his banjo like a shield. And so that was great. Sometimes, it’s the little things that will tell you a lot about someone.

I think, actually, Elle and I had a funny moment. I don’t know if it’s in the film, but it’s where (her character) Sylvie hasn’t seen Pete in a while, and we kind of got that moment in. She tries to hug me and I kind of recoil. You learn things. And I was very fortunate in that Pete’s daughters are alive and live on the east coast, and I was able to meet them. I spoke to Joan, and I got to talk to Peter Yarrow from Peter, Paul and Mary, and even Bruce (Springsteen). I’ve known Bruce for a ling time, and he knew Pete really well. There a lot of people who knew him very well, even back to the time of the early 60s, and so I was lucky I had access to a lot of people’s detailed memories of him interpersonally. His daughter, Tinya, did something wonderful for me. She sent me a recording of him laughing. He had such a distinctive laugh. Those kind of things help, too.

As Pete, how did you find singing and playing the banjo?

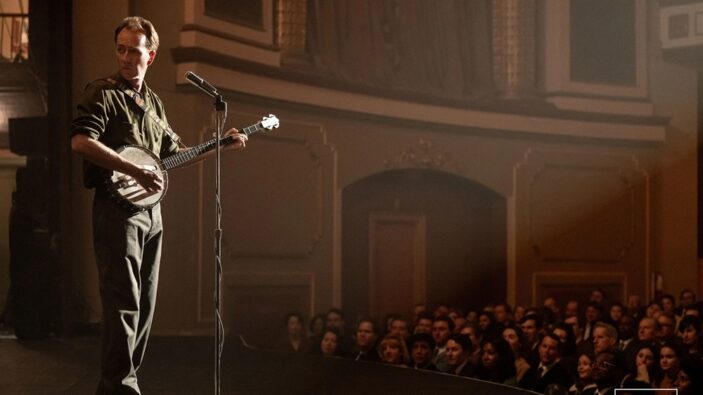

Edward Norton: It was great fun. It was probably the most fun thing about the whole thing. All that immersion is music, I loved it. Everything about music is so enviable. It’s such an enviable experience to have. Even if ours was kind of a facsimile or a proxy for it, it was marvelous. Even between takes, I’d be playing songs with the audiences and the extras, and getting people to sing along. It was just a wonderful experience. I kind of miss it.

Was there ever a moment you felt like you had a grip on the characterization of him?

Edward Norton: That’s an interesting question. That’s an interesting notion. It’s not that you slip in and out (of character), but you’re on the hunt. You’re always hunting for a feeling that you’ve dropped in some sense. I hope on each and every day, in every little piece, that you can find something that’s not about the lines and that anchors your connection or your sense of feeling. It’s very elusive. That’s what this question is pointing at. That what is correct is elusive. There’s a lot of artifice involved in making films. You’re pushing out of the field of your view, all of the artifice, and you’re looking for these moments where even your own sense of disbelief is being suspended. The music helps a lot.

Timothée and I both really loved the duet when (Pete and Dylan) end up playing together at the party. Musically, that was wonderful for us. We really loved that song. It felt joyful. I’d sort of feel connected to the voice. He had such strange and wonderful vocal idiosyncrasies that sometimes his voice was a helpful way to feel inside the skin. But, you know, you’re always chasing it.

James, how tricky is it to make a film about someone as enigmatic as Dylan? To reveal without revealing too much?

James Mangold: I mean, I guess it’s tricky. I felt that it would be a mistake to try to reveal him in the most conventional way of that term. The real question would be not to ask you a question, but what would that mean if I were revealing him? Like revealing he has childhood trauma? Or revealing that he’s got a phobia? Or revealing that he has a secret to tell? In the six years I’ve worked on this movie, reading everything, getting to spend time with (Dylan), talking to many people who knew him, both then and now…my own feeling is that his burden in life, if you will, was that he had a good family, a decent childhood, and grew up in a very lovely place. It always struck me that the thing he was contending with was the enormity of his own talent and imagination, and how that separated him from others. In the same way that someone who is brilliant at football or dance, they go off into their own kind of world (with) that discipline, and it separates them from others. Especially if their talent is as magnificent as Bob’s is.

I don’t think you have to be a Bob fan to acknowledge that the songs he wrote in the period we make the movie, about the ages of 19 to 24, it’s a pretty phenomenal catalogue of songs for someone at that age to be writing and singing. The songs are innovative. They’re catchy. They’re commercial enough. And he wasn’t the vision of what America was buying. He doesn’t look like, you know, Elvis Presley. He’s a really unique character, and following the enormity of his talent drove him into a position where he literally, without any exaggeration, wrote many of the most important songs of the century. And all before he turned 25.

Speaking of how this movie was so many years in the making, and you have chosen a specific time period in his life, which obviously influences the music, but was there a process in selecting songs and them driving the narrative in any way?

James Mangold: It was like thinking of making a playlist tape for myself. I didn’t want three ballads in a row. There were several different songs that Bob sang when he first auditioned at Columbia, and we thought about several different (songs), and Timmy actually wanted to sing “Fixin’ To Die.” Timmy was kind of learning the Bob Dylan songbook, and it was also the song he sang at a Riverside Church, “All Over You.” It was a Timmy selection, and a contrast to “Fixin…”, and they followed each other, so I really wanted there to be a contrast. Also, “Fixin’ To Die” is not a Bob Dylan song.

We don’t go into too much detail in the movie about this aspect, but the folk scene at the time Bob arrived was not a world of singer-songwriters. It was a world of interpreters of traditional songs, on which spiritual and folk songs, and Gaelic and Celtic songs, blues songs, South African American songs were all kind of reinterpreted as part of the folk canon. Most folk albums were not filled with original music, and, in fact, Bob’s first album, only about two of the 11 songs on it, he wrote. It’s hard to conceive now, but that’s not how the world worked then.

Frankie Valli and Elvis Presley, they didn’t write songs. They sang songs. Frank Sinatra sang songs. There was a factory that made songs. And then there were the artists around the arrival of Bob Dylan who were writing for their own voice. We wanted to show how particular his own voice was.

Speaking of Timothée Chalamet, what made you aware that he was right for this role?

James Mangold: Well, there’s a strange quality that I wonder if I had not succeeded in becoming a movie director, I just would have been a gambler. The reality is that making movies is following hunches, following your gut, and, in a way, not paying attention to the stakes involved. The large sums of money of the project, (your) reputation, the way people might annihilate you if you get it wrong. You kind of have to make yourself blind, or dumb, to the ramifications of your actions and just listen to your instincts. That’s a long prologue to say I knew (Timothée) would be good in my gut. I didn’t know he would be good. But I knew in my gut. I guess the right way to say it is I knew he could be great in the role.

I didn’t know how far he’d get with the vocals. I didn’t know how far his characterization would transcend even my very own ambitious expectations, but it’s a factor that Timothée is one of the greatest actors of his generation. On this particular project, he had the blessing and the curse of multiple delays. The first one caused by the pandemic in 2020, which put us on stand down. And then Timothée and I had other commitments we had to fulfill, and when we returned to make the movie again, we were hit with industry strikes and we couldn’t shoot. Finally it got up on its legs in 2024. Timmy had ended up with literally five years more to prepare for this role, and he had the dedication of foresight to carry the guitar and harmonica and songbook and tapes and YouTube videos to study in every other journey he went on, whether it was to land of chocolate or the land of spice.

A Complete Unknown is screening in Australian theatres from January 23rd, 2025.