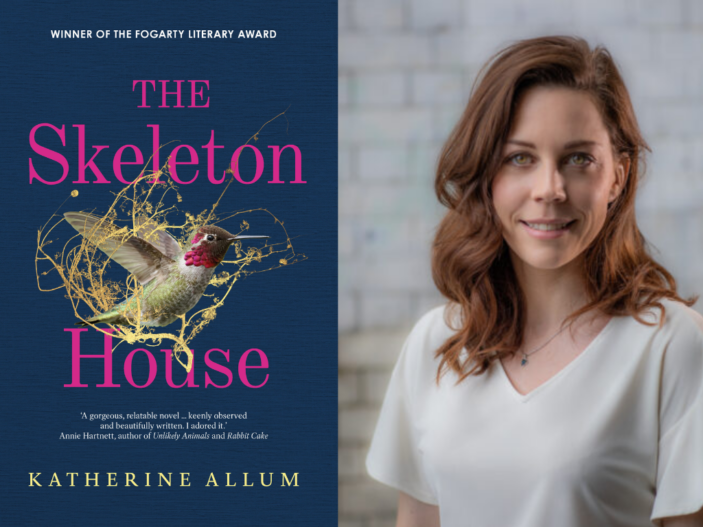

Katherine Allum‘s debut novel was released in May after winning the 2023 Fogarty Literary Award last year. The Skeleton House is the story of Meg, a young woman living in a tight-knit Mormon community in a small American town outside Las Vegas, Nevada.

Meg lives with her husband and two children in a caravan when we first meet her, but they are soon to move to their dream home – the skeleton house of the title- which her husband Kyle is building. But as Meg’s idea of what her life should be grows increasingly at odds with Kyle’s, the dream soon turns to a nightmare.

We caught up with Katherine Allum recently to ask her about this powerful, painful story of resilience and courage.

The Skeleton House is about a young mother named Meg living in St Stephens, Nevada, in a community that largely seems to consist of Mormon families. What drew you to writing about such a setting?

St Stephens is loosely based on my hometown, and similar towns in the American Southwest. Throughout my adolescence, it was a place of frustration and limitations, and all I wanted to do was get out. But after I’d left, I couldn’t stop thinking about the place, and it became clear that a lot of my experiences were not the norm.

I had a vague idea for a novel – the image of these two teenagers on the back of a quad bike, hollering as they roared down a dirt road under the desert night sky – and the two combined and became the foundation of the book.

Meg is herself not a Mormon, and she spends a lot of time with another mum named Carly who describes herself as a ‘bad Mormon’ – what were the challenges in writing about this sort of community from an outsider’s perspective?

Like Meg, I’m OTM (Other Than Mormon), so her general relationship with people in the community is in some ways similar to mine – it’s a small town, which means you have numerous connections with people. The town mortician is the mortician, sure, but he’s also active in volunteering for the Boy Scouts, swims laps with you in the mornings, his son works with you as a lifeguard, and you teach his daughter in swim lessons.

The town revolves around the LDS/Mormon church which hosts many community events, so as an OTM, you can’t help but be pulled in (for example, I sang in the LDS Church Christmas youth choir – stay out on a school night to rehearse, eat cookies, and hang with my friends? Sign me up!). However, there is a boundary, and you do not partake in official church activities.

Writing Meg’s experience was a subtle balance: it’s as if she’s walking on a tightrope, in some ways heavily integrated in the community, and in other ways an outsider. (FYI, the “bad Mormon” label Carly uses is self-deprecating, much like I was called OTM to my face with affectionate humour – and I knew a number of “bad Mormons” with Dr. Pepper habits or other mild vices!)

Readers may forget, because of how much that happens to Meg over the course of the novel, but she’s still really very young and hasn’t long been out of high school herself. Why do you think Meg’s connection to who she was as a teenager — ’The Ice Queen’ — is so key to this story?

This is a great question, and I think it is integral to the story: Meg rapidly went from high school to motherhood, and she didn’t have a buffer between those two identities (such as working for a few years or attending university). She’s simultaneously holding onto that identity because it represents the last time she was carefree and starting to truly come of age/know herself, while also actively burying it because it brings up too many complicated and painful memories. Being on the debate team is especially dear to her heart and identity because this was a source of empowerment.

I love the way that you develop Meg’s relationship with her parents, particularly her father, as the novel progresses — it’s very clear to the reader that her father loves her, but also how wrongly he has misread the situation that Meg has found herself in. Was that a challenge to get right on the page?

It took considerable thought and several drafts to get right. The complexity of this relationship and the way it evolves over time was added in more recent drafts.Meg’s parents are part inattentive, part pushing their own dreams and not listening to hers, and part misinterpreting Meg’s situation and making their own judgement on what she needs. By the end of the book, Meg’s father is finally listening.

The novel contains many fragments, sometimes straight narrative, sometimes sections where Meg appears to be talking to one of her children, and sometimes excerpts from her own writing, with the effect being like reading a sort of journal at times, and at other times, like being inside Meg’s head. Did you set out to write in this style, or was it more organic?

A bit of both! Episodic writing is my style; I can’t write long, novelesque passages. Perhaps that’s why I gravitate toward writing novels and flash fiction, but struggle with anything in the middle, such as traditional short stories.

The variety and organisation of the fragments/episodes was a purposeful stylistic choice. It speaks to how Meg is utterly deprived of intellectual and creative outlets, and as a result, she has built an incredibly rich inner life/voice. Meg views the conversations, bedtime stories, present-day experiences, and past memories blurred together as the way she experiences life.

Originally, half the novel consisted of journal entries and her own writing – I cut 45,000 words during the peak of pandemic lockdown in London. A tiny sliver of this deleted work stubbornly remains at a pivotal point in the novel where Meg “unlocks the vault” and revisits memories from the past.

Within the story, you explore some very dark themes, which I expect some readers will find confronting — I imagine this was also a difficult headspace to occupy as a writer as well. How did you approach this in a way that felt authentic, but also balanced and was safe for your own mental wellbeing?

I reminded myself that this is important. I had to tell Meg’s story, and I couldn’t shy away from writing truthfully and shining a bright light on what is often invisible. Coercive control is under-reported and under-recognised, but it’s dangerous and precipitates the intimate partner violence that we see in headlines. What kept me grounded was an unwavering belief in telling Meg’s story, and infusing as much light, hope, and humour into the book as possible, which provides much-needed contrast against the darkness. This approach is also more realistic and genuine; time and again, human beings prove that in the face of immense suffering, adversity, and difficulty, we cling to what is good, funny, and beautiful.

Have you ever been mutton bustin’? And for those of us who don’t know, what exactly is mutton bustin’?

Sadly, no – my family moved the community when I was beyond mutton bustin’ age and I never got to experience the thrill firsthand!

For the uninitiated, mutton bustin’ is a thrilling youth sport for children ages 4-7. The child is placed on the back of a sheep, which is released to run free, and the child who stays on the longest wins. It’s a popular event at our county fair and typically takes place in the big rodeo ring.

The Skeleton House won the 2023 Fogarty Literary Award, but how long had you been working on the story prior to that?

The first idea/image came to me in 2013, but I wrote the first draft in 2016-2017. Between 2017 and 2023, I submitted widely – to competitions, agents, and publishers – but never got further than a few full manuscript requests from agents. I had long stretches of a year or more where I did nothing because life got in the way. I did a few rounds of minor edits, and finally the one I spoke about earlier where I deleted half the book during the pandemic.

What did winning the Fogarty Literary Award mean to you?

Beyond the initial excitement at winning the award and securing a publishing contract (as wonderful as this was), one year later, I’m just starting to see the true impact.

Most noticeable to my writing life is the confidence boost: I trust myself more as a writer and feel assured that I know what I’m doing. As a result, I’ve written more in the past twelve months than the previous six years since finishing the first draft of The Skeleton House, and Book 2 is almost ready to query for publication.

I’ve been supported and warmly embraced by the astounding WA writing community. I’ve been placed into a fantastic cohort with five fellow debut novelists (the 2023 Fogarty shortlisters) and can’t wait to read their work and see what they do next. If this is what only the first year post-award looks like, I can’t wait to see what’s next.

If you had to do book maths for The Skeleton House (i.e. this book + this book = The Skeleton House), how would you describe it?

I’m so bad at these! Here’s my best attempt: Room (Emma Donoghue) + A Complicated Kindness (Miriam Toews) = The Skeleton House

The Skeleton House by Katherine Allum is available now from Fremantle Press.