Though Becky Manawatu’s debut novel Aue was originally released in 2019, readers may not have been surprised to see it on the new release shelves this past March.

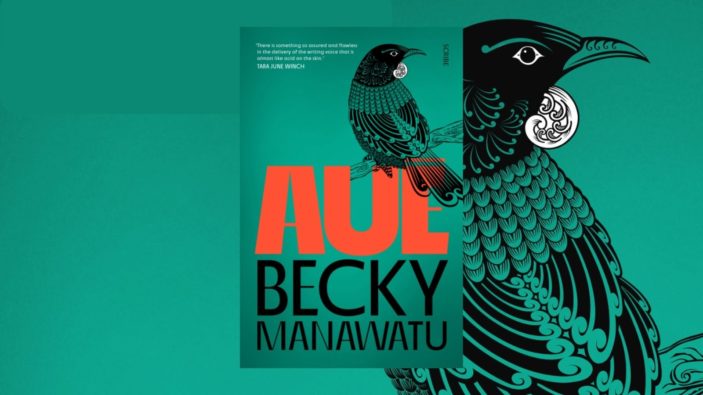

After its original publication by small NZ based publishers Makaro Press, the book went on to win the Jan Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction, the MITOQ Best First Book of Fiction Award, as well as the Ngaio Marsh Award for the Best Crime Novel. It was also widely beloved by many readers. As a result, world rights (excluding NZ, of course, which still belong to Makaro Press) were acquired by Scribe Publishing, leading to this stunning new green edition of the book making its way into the world.

Aue (a te reo Maori word meaning to cry, howl, groan, wail or bawl, as well as an interjection expressing astonishment or distress) is the story of two brothers, Taukiri and Arama. The story begins with Taukiri, who is in his late teens, dropping off Ari (who is eight) at the home of his Aunty Kat and Uncle Stu. Though he knows Aunty Kat will give Ari the motherly love he so desperately needs after the death of the boys’ parents, both of the brothers are wary of Uncle Stu who has a reputation for violence. Then, Taukiri leaves, believing that it is best for his brother he no longer be around.

Ari befriends the daughter of a neighbouring farmer, the tough but surprisingly girly Beth. The two of them are homeschooled together by Kat, until an initiative by local do-gooders arranges for a school bus to take them both to normal school. Beth is sometimes full of alarming violence (our first encounter with her involves the mercy killing of a baby rabbit that has been attacked by birds) and she is obsessed with the film Django Unchained. But, she is also a loyal friend and a stabilising influence in Ari’s otherwise very unsettled life. Beth also has a dog named Lupo, and the three of them form a trio to have adventures. All the while, Ari is wishing for Taukiri to come back for him.

Meanwhile, Taukiri has made it to the city where he makes money busking and briefly working at a factory. His friendship with a musician named Elliott and his cousin Megan, to whom Taukiri feels a strong attraction, brings him closer to the world of gang violence that killed his father and sent his mother into hiding – not that he knows any of this.

Through interweaving the points of view of Ari, Taukiri, and a woman named Jade who is connected to them both, Manawatu tells the story of this family fractured by gang violence; but also evokes a story of brotherhood and friendship overcoming dark times. It is compelling and raw, and very readable.

At times, I was reminded of Trent Dalton’s Boy Swallows Universe, rendering adult violence through the eyes of a child. Both Taukiri’s and Arama’s sections are told in first person, conveying a sense of immediacy. The sections about Jade and Toko use third person, and take the reader back into the events of the past. While these sections are connected, it does take a while for the reader to understand how.

In the last third of the book, a fourth point of view is brought in within these other sections too, using italics to convey a sense of this person speaking to our characters without them being able to hear. While I don’t know whether this voice was strictly necessary, it did add some context to events that were referred to as happening off the page. A sense of dramatic irony is lent by the limits of each character’s knowledge of what is happening to the others in their parts.

While violence in its many forms are a constant thread throughout the book – gang violence, violence towards animals, domestic violence – there are also elements of beauty and gentleness which provide balance to the book. Beth’s father Tom is a balm after the harshness of Uncle Stu and Jade’s gang friends at The House. Meanwhile recurring images of birds, the ocean, and soft guitar music remind the reader that even in times of desperation, love is still possible. The ocean provides a conflicting motif, particularly for Taukiri, who spends most of the novel driving around with a surfboard atop his car but too afraid to enter the ocean after surviving the boat accident that claimed the lives of the boys’ parents.

While Aue might have won crime writing awards, it’s not a typical crime novel, and perhaps sits more comfortably in a contemporary or literary genre. The mystery to be solved is less of a whodunnit, and more of working out the puzzle of this family, and how they came to be fractured in the first place. There is no satisfying solving of the crimes mentioned, and justice doesn’t really get served. But there is something real about this novel, and these people, and the situations they find themselves in.

Read this book if you love great fiction and want to discover a powerful new voice from New Zealand.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

FOUR STARS (OUT OF FIVE)

Aue by Becky Manawatu is available now from Scribe Publications. Get your copy from Booktopia HERE.