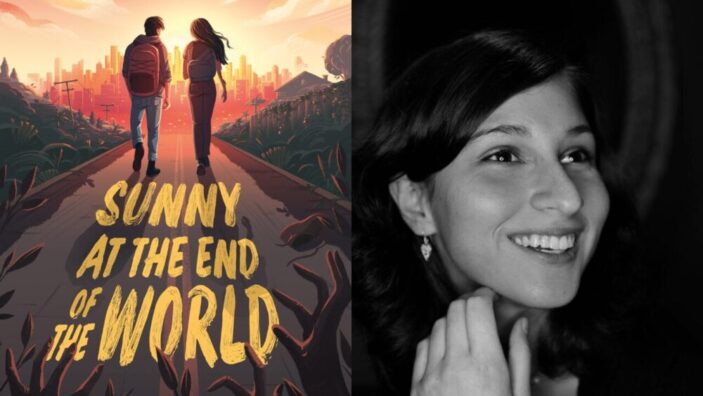

Sunny at the End of the World is the final novel from Melbourne author Steph Bowe. It opens in 2018 with teenagers Sunny and Toby escaping the zombies who’re infiltrating the world and destroying all the adults. Flash-forward to 2034, Sunny is trying to escape an unknown underground facility and find out answers – what happened? who was behind it? was it aliens?

Sunny at the End of the World takes readers on an exhilarating journey right alongside Sunny. It’s a story of grand stakes and surviving the zombie apocalypse.

Unfortunately, it’s also a posthumous release. Bowe passed away on 20th January 2020 at the age of twenty-five following a battle with a rare form of non-Hodgkins lymphoma. Bowe was a YA writer from Melbourne and the author of multiple award-winning books.

Her impressive storytelling is adorned with humour and endearing characters. Girl Saves Boy, her debut novel was published in 2010, followed by All This Could End and Night Swimming; the latter was longlisted for a Sisters in Crime Davitt Award in 2018. The manuscript of Sunny at the End of the World was discovered on her computer by her mother and sister.

Sunny at the End of the World is full of Bowe’s trademark humour, impressive storytelling and filled with likeable and endearing characters. It also features some uncannily accurate predictions of an ‘outbreak’ similar to the one we all experienced in 2020.

Sunny at the End of the World is out now, read the extract below and run to your nearest bookshop to get your hands on a copy of your own!

![]()

Sunny

2018

Hope started to creep into my heart. We had fuel in the car. The highway was driveable, despite some strewn corpses and the odd abandoned car. And we’d located what we thought was the right monastery on the map. We were less than an hour away. If Toby—inept, nervous, lover-not-a-fighter Toby—had managed to survive a roomful of teenagers turning into zombies and weeks lugging a baby around without so much as a close call, it was not absurd to assume that his mother might similarly have survived. A family with good luck, unlike mine.

I scanned for radio stations, but there were none. I reasoned that radio hadn’t been good in years. Hardly a great loss. Ronnie slept. I found a stray muesli bar in the car for Toby. I hardly even thought about eating human flesh.

Then, halfway to the turn-off, we heard a strange sound, something coming from beneath us. The sound of people marching. I wound down my window and strained to hear. Toby realised what it was before I did. Perhaps my hearing had declined, or could he see up ahead? We were a few kilometres away, I had to squint to work out what it was.

When we got nearer, Toby stopped the car. We sat in silence.

Thousands of them. Stumbling south. So densely packed they blocked the highway and were trampling each other, which explained those bodies we’d seen earlier on the highway. The only sound was their footsteps, an almighty rumble.

‘Fuck,’ I said.

‘Language,’ said Toby, but his mind was elsewhere. ‘We’re not going to get past that,’ I said. I fumbled for the map, found the monastery, and ran my finger back through the township, towards an earlier turn-off.

Hyperventilating, Toby turned the car around. ‘Calm down,’ I said. ‘You can take the last turn-off we passed. It’ll be a bit longer, but we’ll still get there.’

We returned the way we came. ‘What if they go into Byron?’ Toby’s voice was high-pitched with fear.

I shook my head. ‘I think they’re going to stay on the highway.’

‘They’re like lemmings,’ he said. ‘If we can’t stay in Byron, do you think we should stay behind them? Or try to get ahead?’

‘Maybe take the other highway,’ I said. ‘Where should we go?’

‘There might be a group on the other highway as well. Grouping must be standard behaviour for them. Maybe there are hordes everywhere.’

‘Where should we go, Toby?’ I repeated. ‘Wherever there would be a state emergency response,’ he said. ‘The first place the government and the army would swoop in and start saving people.’

‘They’re not going to take me,’ I said. ‘Sure they would,’ he said. ‘They could make a vaccine from your blood. You could save everyone. We could all be super zombies like you.’

‘Do not call me a super zombie,’ I said.

‘I’m sorry.’ He glanced in the rear-view mirror, but I already knew the horde would be out of sight. Though definitely not out of mind. ‘Canberra,’ he said. ‘It would have to be Canberra. They would be protecting the prime minister.’

I shook my head. ‘I disagree. Sydney is the most populated city in the country, with the best infrastructure and the most established urban army base. We don’t even know that the prime minister is in Canberra. Was Parliament sitting when this happened?’

‘A more isolated place than Sydney would be better,’ he said.

‘No one is in Canberra to help us. Isolated means alone. The more people there are, the likelier there’ll be a significant number of survivors, or whatever we want to call them. Sydney is the go. Plus, it’s closer.’

Toby took one of his hands off the wheel and held it out to me as a fist. ‘Rock paper scissors,’ he said. I shook my head. Leaving our survival up to a random game of chance? Great way to die sooner. ‘Rock. Paper. Scissors,’ he repeated, more forcefully.

I made a fist. I tried not to think about how colourless I had become. ‘Rock, paper, scissors,’ we said, in unison.

![]()

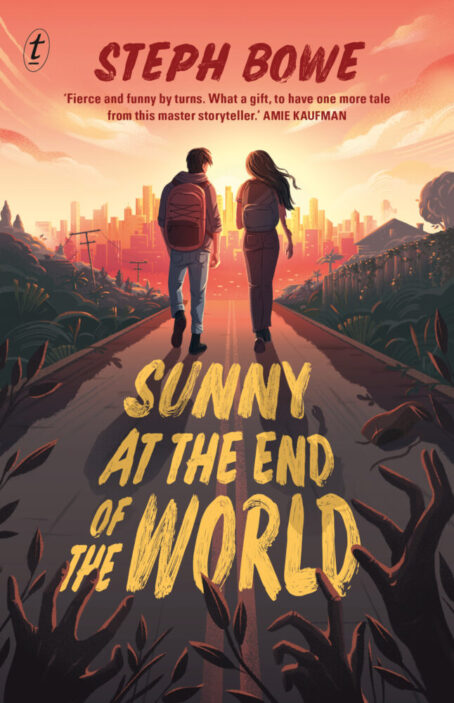

Sunny at the End of the World by Steph Bowe is available now from Text Publishing. Grab yourself a copy from your favourite local bookshop HERE.