Sexually repressed, separated Greek girl on a rampage. There’s no love here, just fucks. But is she fucking him or fucking herself? Koraly Dimitriadis’ work was first published as a zine in 2011. It quickly sold out of stores. Now reissued as a book with extra poems, her first erotic verse novel strips itself down, pulls you close, and explodes — both with you, and at you.

Love & Fuck Poems is a collection that explores tensions: sexual, cultural, familial, and gendered pressures are held up against one another until they’re spitting in conflict or sparking with similarities. It is an emotional self-examination with a hand-mirror. What we see is a vibrant and visceral story of a woman scrutinising herself from every angle, and realising that she can’t look like a “good girl” from all of them.

Dimitriadis’ novel plays with our desires as readers. Comfort is rarely given. Pieces like the violent and venomous “How To Get A Fuck” are followed by the simpler “Freedom”, yet the latter is hardly reassuring — if anything, the shift in mood is disconcerting. We get the impression that we’re being appeased, not pleased.

It is this sensation of being nearly-but-not-quite-satisfied that tantalises the reader, and encourages us to keep searching, even though we’re not sure what we need to get over the edge. Maybe we’ll find it with the next poem. But as the levels of intensity and intimacy fluctuate, often quite independently of each other, we start to understand how ‘love’ and ‘fuck’ can be two very separate concepts. All of a sudden, our motivations are startlingly similar to those within the book.

Perhaps one reason why Love And Fuck Poems is so relatable is that Dimitriadis’s writing is so raw and passionate. By rejecting many of the academic conventions that the form is still measured by, she has written poems that are accessible even to those who don’t often read poetry — the universality of her themes, coupled with the intensity of her personal experience makes for a powerful read. This uncompromising collection will have you wondering: Are you reading this book or is it reading you?

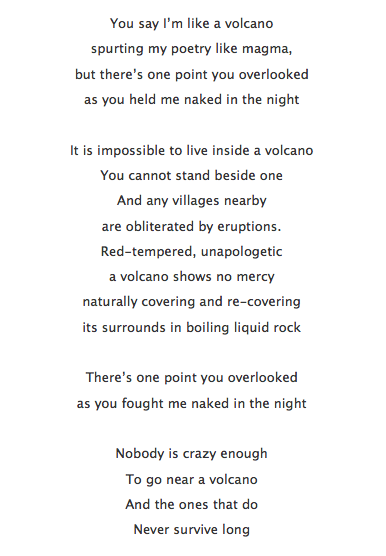

Excerpt: Volcano

Question and Answer with Koraly

Love and Fuck Poems — Awesome title. When I was reading through your book the first time, a colleague saw the title and remarked, ‘But aren’t they [‘love and fuck’] the same thing?’ In response, I found myself saying that I interpreted it as two themes sitting side by side; very similar in some ways but very different in others. This concept also comes through very strongly in individual poems. Would you say that this is an accurate (if simple) way of explaining it? If not, then how would you explain the two ideas in the title?

Wow, great question! I think my upbringing has a lot to do with the title. I was brought up in a conservative Greek family and sex wasn’t really discussed except that you had to be a virgin when you got married. I also wasn’t allowed to have a boyfriend. A boy was a “friend” until he was “a husband”. I wasn’t even allowed to watch kissing to television. So when I got married and did what was expected, and lived the life I was expected to live, when it all fell apart, the repressed girl inside me exploded out and the words came out raw and unapologetic. To me, the title is “these are my words, and I am not shutting up anymore.” But there are many layers to the title of the book. I don’t want to be didactic about what the title means. I prefer readers to interpret the story and the title in their own way.

Your poems shift between different styles – some have a more narrative element (such as “Domination”), some utilise space as a means of expression (such as “Addictions”), and some focus on the intimacy of the thoughts (such as “Your House”). Do you think this is a result of different situations requiring different forms to feel right? Or was it a conscious choice to give the collection more diversity?

I see this book as a verse novel, a story told through poetry. On some days we are angry and want to tear the world apart, on other days we are regretful of our actions, on other days we are in love. Sometimes things are summed up in a few words. Other times we need a lot of words to describe what we feel.

In “My Words”, you make reference to (include, even) your earlier poems. What would you say are the biggest ways your poems have changed since you began writing?

I think the major turning point for me was when I gave myself “permission” to be a poet. I have been writing poetry my entire life, but I thought a poet is someone who studies at university for many years. There were two people who encouraged me to give myself this “permission”. Maxine Beneba Clarke, a friend of mine who is a poet is the first. I was in her living room one day and I said “Maxine, I wrote this poem, and I feel like performing it for you, do you want to hear it?” I had never been on a stage before. Maxine heard the poem and said “You should be on stage, get out there and perform.” I questioned her on my ideas about what poetry is and she dismissed them all. “You are a poet,” she said. My other influencer was my poetry teacher at RMIT TAFE, Ania Walticz. I had never taken a poetry class before. I went to the first class and said “okay, Ania, I want to be a poet, teach me the rules.” She said, “There are no rules. If we all followed the same rules we would all sound the same and how boring would that be?” Both of these events occurred at around the same time. That’s when I gave myself “permission” and that’s when the flood gates opened. I wrote over a hundred poems that year.

So who are some of your favourite poets, and poetical influences?

I love Sylvia Plath for her rawness. Margaret Attwood, Rumi, TT.O, Charles Bukowski, Jas Duke.

You also present monthly on 3CR’s Spoken Word program. How would you say this has influenced your writing style?

Being a presenter on spoken word has allowed me to scout for and connect with other grass roots poets and to learn more about their stories and how they came to writing. Many times I have been inspired by the poetry and the stories shared with me and it has influences my writing and my performances. For example, I heard Ben John Smith perform at Passionate Tongues and had him into the studio very quickly. At that point I was writing poetry but not sex poetry. I didn’t even know you could write sex poetry. I had sex scenes in my unpublished novel, Misplaced, and my mentor, Christos Tsiolkas had told me I know how to write sex really well but it never crossed my mind to write sex poetry. Ben’s writing influenced my direction and I asked him if he could launch my zine, Love and F**k Poems. I suggested I do a poem and then he respond with a poem of his own. That was how our annual poetry wars were born.

Let’s get into the details. One of your poems that really stood out for me was “Push Through”. In addition to the way the form of the poem slowly evolves from a flowing rhyme to a mantra of sorts, there are also several different relationships that are unexpectedly grouped together — the man of dreams, the daughter, vs the emotionally unavailable, and the solitary self. In a way, these not-quite-contrasts made it felt like the most ‘love and fuck’ poem in the collection. Is there any backstory or insight into this poem that you’re comfortable sharing?

I would say that push through is one of the turning points of the narrative. It’s when the protagonist has exhausted herself chasing after men and can see a small white light but there is all this emotional baggage stopping her so she has to push through it. Nobody can make it better. This is the light. Pushing through and embracing this idea is a difficult thing to do. It sometimes takes an entire lifetime to do. Back then when I wrote that poem I knew that was what I was aiming for but I didn’t know how to push through to get to it. Today I can say I have pushed through it, using my words.

Many of the poems make reference to behaviour: obedience, sub-ordinance, and the phrase “good girl”. However, the ideas are often reintroduced from different perspectives (like the self, father, lover), giving the impression that being “good” for one person involves being “bad” for another. The only instances we see them somewhat reconciled are in moments of pain (such as in “Threesome”), making the relief the reader hopes for a very overwhelming and emotionally scrambling experience. Does this reflect solely upon personal pressures, such as relationships and motherhood, or a wider span of pressures that may impact your life, such as being a woman, and your cultural background?

Wow. Another amazing question. I can see this book has moved you and touched you and this is why I write. The book in itself, for me, is making a general statement to my culture – that I am a woman and I am going to do and say whatever I want. There are not many female writers from migrant cultures writing in such a raw and confronting way because we are taught to be good greek girls. But growing up, good greek girls rebel behind their parents backs ie they might be dating men and having sex which is considered very “bad” by their culture and parents but “normal” for many outside these cultures.

I think that rebellion and badness always stays with a good greek girl. The norm is that the “bad” is hidden unless you are caught out. In my case I am putting the bad out in a book and saying I am being “bad” and I don’t give a “fuck” what you think. But is being in love and having sex “bad” if you are unmarried? In my culture, it is bad. On the other hand I love being Greek-Cypriot. I guess you could say I have a love-hate relationship with my culture. Growing up it was more “hate” but lately it has been more “love”. I think because in recent years we have been more able to understand the migrant experience. They left for a foreign place and they clung onto their old ways because they were so afraid. In a sense, it was anxiety driven. These ways were then enforced onto their children. But these days I think my culture acknowledges what has happened, and has relaxed a bit.

In your Acknowledgements, you thank your editor [Les Zigomanis] for being ‘tough’ on you. Was the editing process difficult? How much of an impact did it have on your poems?

Because I am such a raw writer, I knew I needed an editor who would, in turn, be raw and confronting with me. The original zine was unedited because I had no plans for it other than to sell at gigs. It was a complete surprise when they started to sell like hot cakes. This led to me reconsidering the zine for a book. But I knew the zine needed editing and more poems to strengthen the narrative. Initially Les had published a short story of mine some time back. One day he made a comment about one of my poems on facebook and said that he felt sometimes I “hold back”. I couldn’t believe he thought I was holding back, but I wanted to know more about why he thought that. We worked on the poem together and from that I asked him if he would be interesting in editing the deluxe edition. When you have two raw and confronting writers working together, one is bound to end up dead

I hear you’re also currently working on a verse novel titled Good Greek Girls. Is there anything you’re able to share about that?

I have a novel, Misplaced, which I have been working on for eight years and I am currently looking for a publisher for that. I was mentored by Christos Tsiolkas for this project. Good Greek Girls is a follow up to Love and Fuck Poems. It is a story told through short stories and poetry. I see Love and Fuck Poems as a snapshot in time. But Good Greek Girls takes a reader on a longer journey:

“Kaliopi is married and thirty-two and she doesn’t know what do. She sits with her baby girl on her knee in her white-picket northern suburbs luxury. Maybe she should just stop wallowing, and just start swallowing the pills she stopped taking to her pregnant. She just wants to be normal or else, what’s the alternative?”

With My Australia Council ArtStart grant I am also embarking on a project I call “The Good Greek Girls Film Project” which will see four of the poems in Good Greek Girls turned into films. I envisage them to also be amalgamated to create a book trailer for Good Greek Girls.

—

Book Publisher: Outside The Box

Release Date: 2012

RRP: $18.95

Formats: Paperback, audiobook, e-book.

Purchase From: http://www.outsidetheboxpress.com/

—

Poem “Volcano” reprinted with the permission of the poet, Koraly Dimitriadis.

———-

This content has recently been ported from its original home on Arts on the AU and may have formatting errors – images may not be showing up, or duplicated, and galleries may not be working. We are slowly fixing these issue. If you spot any major malfunctions making it impossible to read the content, however, please let us know at editor AT theaureview.com.