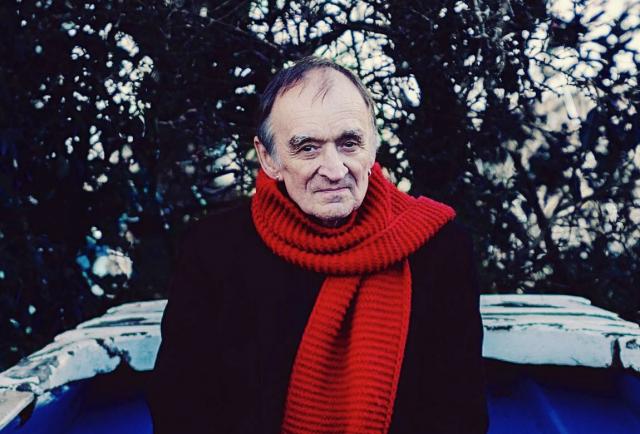

Martin Carthy is rightly considered by many to be one of the most influential figures within the British music landscape, and continues to be a leading figure in the English folk tradition; having recently been awarded the Lifetime Achievement at the 2014 BBC Folk Awards. Carthy has released over 40 albums throughout the course of his career, with another, The Elephant, a collaboration with his daughter Eliza due for release in May.

Ahead of his exclusive appearance at next month’s National Folk Festival, we caught up with Carthy to discuss Folk music, it’s many revivals and resurgences and his appearance at next month’s festival.

Congratulations on the Lifetime Achievement Award. I imagine you’re not quite ready to hang up the guitar just yet?

Oh thank you. No I don’t think so. Can’t do that. Too much to do.

Yeah just looking at your touring schedule you’ve got a fair bit going on later in the year and you’re releasing a new album with your daughter in May and then coming over here to Australia in April, so you’ve got a busy couple of months ahead of you too.

I like working. Yeah, It’s just keeping working all the time. It’s a great life. I don’t think musicians retire do they? (laughs) It would be a weird thing to do for me.

What is it that still drives you to continue playing?

The desire to get better at my job if you like, physically it’s different to say the least, but mentally; it’s just beautiful music and I don’t want to stop playing it, and I don’t want to stop playing it in public either. I’m a non-driver so I have to go everywhere by train, and sometimes the journeys are a right pain in the neck. But the gigs at the end of it are just fantastic, that’s why I do it.

You’re going back to revisiting old partnerships in a way as well. I see you’re touring with Dave Swarbick again at the end of the year.

Yeah we do. We’ve been doing that since ’88 or ’89 – ‘88. He suggested we do a tour together, and on that first tour, that was ’88, we basically revisited all the stuff we had done in the sixties. We had a talk about it, he was perfectly happy to do that, at least he said he was, but I said I couldn’t see the point of it; and we came up with some new stuff. And from thereafter he was the leader; it was a case of just finding stuff that was new to us to do. And if we were revisiting new stuff we were playing it, without insulting our 1960s selves, we were playing it like grown ups. We were playing it like people who were twenty-five or thirty years older; and that was very exciting.

I was wondering if you were managing to find new songs, or at least songs that were new to you, even after a career as long as yours?

Sure. Sure it happens all the time. That’s the great thing about traditional music, it’s so varied, and there are so many different ways of doing so many songs. I find that suddenly I walk into a song I think I’ve known all my life and I’ll suddenly realise what it’s about. That is very exciting. And the ones I’ve been doing forever and forever will suddenly reveal something new. That’s what happens when you get older. It’s fantastic, to use a really boring word, but it is fantastic.

I suppose as you get older, or you have new experiences you get a new perspective on some of these songs.

I think basically it’s like that yeah.

Folk is a term that gets bandied around a lot these days, with anything with an acoustic guitar getting labelled folk. Everybody seems to have his or her own interpretation of the genre. How do you define it?

I suppose its songs that have a bit of history to them. They’ve been through a lot of people’s hands. It’s not necessarily true that you can’t know the author, because the authors of some of those old songs are known. But it’s what’s happened to them since they were launched onto an unsuspecting public anything up to a 120 or 130 years ago. I know those mining songs from the North-East of England were written by one bloke. Some of them, they’ve changed over the years and that is what’s interesting about traditional music.

I used to mind when people, when the music business, purloined the term folk. But now I don’t care anymore. It doesn’t really bother me. Back then I would say that there are no labels and that we’re all in it together la di da di da, and then get pissed off when somebody called something that I didn’t think was folk, folk. Which is daft isn’t it; a silly way to going about things. What I talk about these days is traditional song or just very old songs, because they’re what interests me.

I like some of the other stuff that is coming along, and there are others that I don’t particularly find interesting. And I’m not crazy about this idea that people, or the business often will measure people by their capacity to command a stadium. That to me seems ridiculous, and very little to do with music, it’s about putting on an event. That’s fine, for people who want to be a part of that. OK, that’s OK, but for me it doesn’t seem to have much to do with the music. And music is what I love.

I always answer a particular question in the same way. The thing that made me decide to want to sing all this old stuff was when I saw this Norfolk fisherman singing in London. Ewan MacColl brought him down to the Ballads and Blues club in the very late fifties. I was a kid. I was a kid and I saw this bloke sing, this 80-year-old man sing and I was absolutely thunderstruck at what he could do, the amount of passion there was there and the way he played with the audience. He was amazing, absolutely bloody amazing. That sort of connection is something to strive for I think, to connect with an audience like that is something to really strive for and aim towards.

I wonder if it may be more difficult to play on those smaller stages and connect with every single one of the audience, than to play on those big stages.

I’m not sure. I’m never super comfortable on a big stage. I’ll do it every once and a while and I’ll prepare beforehand, make sure I know exactly what I’m going to do, because you have to. But you have to assume that the people there don’t want you to fail. I had to come to that understanding with myself after a while, because I was so so uneasy playing those big stages. So once I did that I was OK, but give me a smaller audience any time.

There’s nothing quite like that electricity you get from an audience that is sometimes standing less than five feet away. There’s nothing like it. It’s a case of, as they say up in Yorkshire, Shit or Bath; and it’s wonderful, the electricity that you can give out and that comes off that audience is astonishing. I love it.

I guess it’s that whole thing of there’s nothing to hide behind

Absolutely, well you’ve got some fantastic songs that you’re lucky enough to know. And if you have any sense at all you appreciate the value of this stuff. And if you can impart that to that crowd who are standing five feet away, oh boy, you’re in for a great time (laughs).

Are there still opportunities out there for those smaller shows in the UK? It seems like a lot of the folk scene is centred around the summer festival circuit.

Sure. Well that’s true. Back in the old days the folk clubs fed the festivals, these days the festivals feed the folk clubs. The folk clubs are still there, but they’re not the leaders they were. The nature of them has changed a bit, but they’re still as great. A lot of them still operate without a PA, which is very unusual. Back then having a PA was really unusual, and you had to learn how to deal with it, and the PAs weren’t that good anyway. But you just dealt with it. Now a lot of them, it seems to me, operate with a PA.

Folk music seems to go through cycles of popularity, you’ll no doubt have seen this throughout your career, what do you perhaps attribute to this latest revival in interest to the genre?

Well, it’s a mixture of things. Eliza and her contemporaries seemed to restart the thing I suppose, in the late eighties early nineties. Eliza is now thirty-eight and is regarded as something of almost an elder statesman. But there’s a whole bunch coming along in their early twenties. And so many of them are women and so many of them are so good. There are a good number of blokes too, but the ones who are really brilliant were the couple of exceptions like Alasdair Roberts, who is wonderful. But so many of them are women. You’ve got Bella Hardy and Lucy Farrell, they’re just bloody wonderful. And Eliza of course (laughs)

There seems like there a lot of artists and groups, like yourself with Imagined Village, who are trying to push the boundaries a little with folk music, to still remain true to the traditional but also try to be innovative as well.

It just shows you, you can do anything with a traditional song. You can’t hurt it. You can sing it badly, then it’s up to someone else to come along and sing it properly, but ultimately I don’t think there is anything you can do that is going to damage a traditional song. A lot of these lasses I was telling you about, people like Bella and Lucy are the sort of the people… Eliza has just done an album and touring with this thing she calls “fiddlevilles” it’s Carthy, Farrell, Hardy and Young. They all of them have a slightly different view on the songs, they’ve just taken an old idea and figuratively speaking taken a step to one side.

There’s a lass called Stephanie Hladowski who’s amazing. She’s weird as weird can be, but Jesus Christ it’s so exciting to hear somebody who thinks differently. And it reflects on what I would call popular traditional music, because there is no single way, if you listen to traditional song there is no single way or single style of singing. There’s this whole panoply which humanity gets up to, this whole thing they do. Nobody sings a song quite the same, nobody sounds like anybody else, and everybody has a different view. Which is what seems to be happening with this current crop of new singers, I’ll call them new singers, but some of them have been around for six or seven years now. But it’s very exciting.

It’s interesting though, there seems to be a reticence from some fans within the tradition to embrace these changes. One of the comments on a YouTube video of Bellowhead playing at the Folk Awards was “This isn’t Folk music, it’s pop music”

There are people who are upset. There always have been and always will be. And when they say its “pop music” they mean it’s rubbish. People used to say that in the sixties. You had people around like The Beatles and Dusty Springfield, you had fantastic singers and innovative performers; so you couldn’t really equate it with rubbish. You could just say you didn’t like it? Why not just say that?

There are people who aren’t going to like Bellowhead, I mean I love some of their stuff, and I’m not crazy about others. I think there a people who think that way about what I do (laughs) it’s perfectly reasonable. But to say it’s pop music. It’s unfortunate.

It dawned on me a few years ago that what happened in the wake of the demise of skiffle, there was this explosion, revival-stroke-explosion of popular music. That is to say music of the people, and that music of the people spawned, the folk revival, the beat boom in the sixties, people like the Beatles, some of them brilliant, some of them ordinary, some of them OK. But that’s what happened. And that’s what happened with jazz too. They’re all working class movements and working class musics.

It’s wrong to just slap them all down and say they’re all rubbish we’re brilliant, but when I was twenty I would say that about what I was doing, when I was sixteen even, me and my mates were all rubbish and all those people who could really play would come and tell us we were, and we’d just look at them and think “You don’t know anything, we’re brilliant, you’re just stupid” and hopefully you grow out of that notion. But this whole thing was an explosion of popular music, of ordinary people making music, some of it was wonderful and some of it was traditional music. If the genres get mixed up, then that’s interesting, sometimes it’s not interesting at all, but that’s what happens.

We were talking about Imagined Village earlier on, that’s the sort of thing that can happen and can make for some very interesting things and can teach, when I work with people like Imagined Village it’s a fabulous learning opportunity, why would you turn your nose up at that? Why would people get so upset, I mean I get why they get upset, they’re very protective, I think it’s because they can’t quite believe that you can’t hurt this music, and you can’t, you can’t hurt it, you can do it badly but you can’t hurt it ultimately.

I think one of the reasons. I remember back in the Eighties, when we were dying on our backsides. The audience was just getting old, fatter and balder; and I remember there were suddenly these eighteen to twenty-four year olds looking terribly embarrassed to be sat amongst all these old gits. But they obviously really wanted to find out about this music. A lot of the music press and a lot of the DJs were basically saying how Folk music was a joke, and a lot of these younger people were thinking “You’re a joke, so if we think you’re a joke, the stuff you think is a joke, is worth investigating” and that’s what they did.

Those are the people who are the engine room for what’s going on now. That for me is endlessly fascinating. It reflects what happened to me when I first heard this guy Sam Larner, I was seventeen, and I wasn’t in a room full of seventeen year olds. There were maybe a couple of other people my age, who were equally blown away by Sam Larner, and look what happened there. There are all sorts of reasons why people go investigating other music I think, and that’s a fascinating one. I went along almost by accident, I went along with a friend who had conned his way onto the evening to perform, and he performed really badly and disappeared, so having gone with him, I went home on my own, because he’d buggered off. So I stayed to listen to this old man, and it’s the best thing I’ve ever done.

It is interesting how you end up coming to different music and different genres. My discovery of folk music, coming from Devon, came via listening to Seth Lakeman, and then branching out from there.

Yeah, that’s what happens. It’s an exciting journey isn’t it. Where something can take you is quite extraordinary and it can be way away from Seth Lakeman, but you still retain that affection, that admiration for what brought you there in the first place. It’s great. It’s endlessly fascinating and you could talk about it all day.

You mentioned earlier that you weren’t a huge fan of festivals, what was it that drew you to the National Folk Festival?

I like coming to Oz. I love to coming to Oz and I haven’t been since ’99 and I’ve missed coming. First time I came was ’79 and then there was a ten year break before I came again, then I came ’89 ’90 ’94 ’95 and ’99 and I just really enjoyed it. I head all sorts about it. And its very mind broadening, because the National Festival has all sorts of things it’s like a version of what goes on these days at US festivals. Because there are so many people and so many different strands that it’s not just the same versions of the songs I know and love.

When I first went to the States I thought that was the way it was, and that’s the way it should be. Then I finally woke up to the fact that’s many different strands that make up the USA and all sorts of different strands that make up Australia, and it’s reflected in the National Folk Festival. Once I got hold of the idea it was truly mind broadening. Wonderful.

I love it. It’s an opportunity to reconnect with some old friends, and a chance to come over to Oz. Yes please (laughs) it’s not like, I’m imagining, that it’s not like a lot of the festivals where you’ve got one massive stage and lots of workshop stages, it different from that. Last time I was at the festival I remember noticing how many smaller stages there were so people could operate properly. It was nice and people were very welcoming.

So other than touring, what does the rest of the year have in store for you?

Just to go on working, just to keep on touring. I enjoy touring and I enjoy standing up in front of an audience and singing. It’s a great life.

Great! Well thanks for taking the time to have a chat with me today, it’s been brilliant. Enjoy the festival.

Thanks Simon.

———————–

Don’t miss Martin Carthy at The National Folk Festival. It runs from 17th until the 21st of April. For more information visit http://www.folkfestival.org.au/

———-