Throughout his directorial career, Steven Soderbergh has so often gone against the grain. From his avant-garde arthouse approach in films like Sex, Lies and Videotape, shooting the entirety of the psychological thriller Unsane on an iPhone 7, to acclaimed studio franchises like the Ocean’s and Magic Mike trilogies, he indulges in the unexpected. And his latest venture is no exception.

Shot entirely in the first person perspective of a ghostly figure haunting a suburban household, Presence is an unconventional genre piece, with Lucy Liu and Chris Sullivan as a married couple who are convinced that they and their children are not alone in their new dwelling.

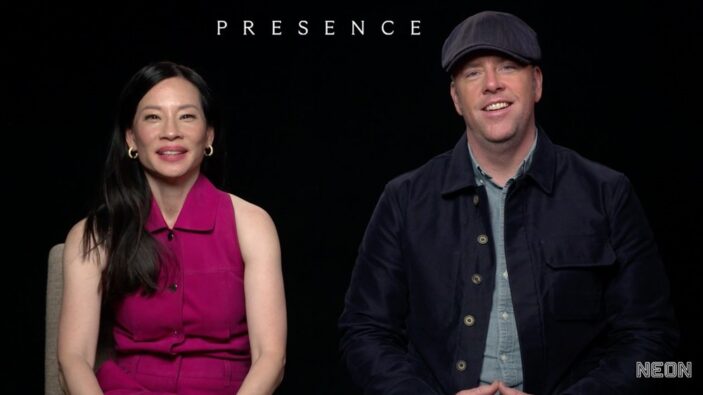

As the film begins to haunt Australian theatres (you can read our review here), Peter Gray spoke with both Liu and Sullivan about working with their famed director and if they have seen their perspective on human connection alter as a result of shooting the film.

This movie was actually the first movie I saw at TIFF last year.

Lucy Liu: Oh good, oh that’s so great.

And one of the things I liked about it was that there’s this perspective on grief and human connection as one of its main thematics. I wanted to ask both of you if you came away with a new perspective on grief or human connection in a way that you’ll carry forward in your life?

Chris Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. You know, I think the interesting part about this particular horror movie, for lack of a better genre, is that the fear mechanism in this movie is grief and loss, and it’s about a person trying to put it off. Trying to maybe avoid it. It is about a young girl who is facing it head on. It’s about a young boy who is feeling disconnected from his family. And it’s about a father who is feeling disconnected from his partner.

Horror movies have always been a safe place to face our fears, and in this particular movie, having been a part of it and having watched it a couple of times, it’s important to face grief and not just tuck it away. To not hide from it. We have big griefs and little griefs in our life that all need to be dealt with, or else they haunt us.

Lucy Liu: So well said. I think that the thing about loss and grieving is that it’s not linear. It’s quite syncopated and unexpected. If you don’t feel or allow someone else to grieve and you want them to just move on, you’re missing such a big part of what humanity is. I mean, nature is about loss, right? So, there’s the flowers, then it changes into summer, and then it goes into winter and fall. The seasons change and that already shows you what loss is. Humans don’t want change as much, and I think there’s a lot of power in this movie as well. There’s a power struggle. (My character) wants to have power over her son, and she doesn’t want to deal with her husband. There’s a lot of people trying to gain control of the situation, and the game is that everyone’s playing a different game.

There’s this lack of community within the family which creates the dysfunction, and when one does feel loss, it’s an opening to create space. And sometimes it has to be forced, and in this case it is to allow for more. And if you don’t do create space for yourself or for other people, it only chokes the progress or the growth, you know? You don’t necessarily move on. That infestation stays. You have to let the change happen, because grief changes into other things as it should. I think David (Koepp, writer) does a really excellent job of showing that within the genre. It’s unexpected, and it almost feels dangerous, because it’s presented as a sadness that isn’t resolved before turning into something quite horrific.

Lucy, your character says in the film a few times about how “time is all you need.” What’s your take on the notion that time heals everything?

Lucy Liu: (My character) Rebecca is all about planning, and I think she’s also in denial about the pain that her daughter is going through. She’s not being as open to connecting and communicating with her as much as her husband is. He’s sort of, like, “We need to really engage with our children to really help them move through and process.” I think we learn later that she understands that by force, because of her own loss, and she’s so pragmatic about it when she’s saying it. It’s kind of an illusion to just shove off, because she really shows so much favouritism towards her son, and her husband is somebody who understands his children and sees them equally. He loves them both, and she doesn’t really have as much compassion, right?

Chris Sullivan: Yeah, everyone in this family is coping in different ways, you know? He’s clearly putting the wine away, you know. Like, he’s coping in a different kind of way. I guess what you hope for at the end of the day is that everybody’s coping mechanisms in a family unit are able to help each other. And in a way, they kind of do. There’s dysfunction, as there always is, but there’s also love.

What did you both think when Steven first approached you about these roles?

Lucy Liu: I had no God given idea why he cast me (laughs). Maybe because they were shooting on the East Coast and that’s where I was…

Chris Sullivan: Because he loves and respects you as an artist. Maybe that’s why Miss Lucy Liu.

Lucy Liu: It’s funny, because he didn’t say it was horror. When I sat down with Steven, he talked about the script a little bit. We talked, but he didn’t say what the role was. So when I read the script, I thought the spiritual woman who can connect to the other side was who I was considered for. I just assumed it was that role. I mean, she’s a little bit kooky and interesting, so I could see why he wanted me to do that. I had some ideas about it, and then I reached out to the casting director and I asked, “Which role is it?” I was then told it was Rebecca, and then I went back and re-read the script, because now it was completely different.

But when I read the script, it was not something I saw as horror. I thought of it as more of an intimate conversation between a family, which can be terrifying. I didn’t really know it was horror until it was done, and then it was presented as that. To me, it was about this separate entity overseeing what was happening with this family. That then created this ending, which I still didn’t see as a horror movie. To me, I think it’s more of a suspense.

Chis Sullivan: I tell people it’s a ghost story. It’s a ghost story in all kinds of ways to me, and as far as being surprised by anything Steven Soderbergh decides to do…I have no surprise. If you look at that man’s IMDb, everything he has done is a surprise until you realise that everything he does is him challenging himself in a new way. He is trying to do something that hasn’t been attempted before. I think the only thing that would surprise me about anything Steven decided to do, was if he retread old ground. That would be surprising. But this is a feat of cinematic execution on his part.

Lucy Liu: The thing that you said is so interesting, is that what would surprise me if he just, like, gave up? Like, I don’t want to do this project anymore? I think that he puts himself into something. He loves the challenge of (it). I can’t speak for Steven, but judging from what I’ve seen, he puzzles things together to make it work. And if he sees something that’s not working, he then sudokus it together (laughs). There’s a way that it will work. If it’s not tangible, he’ll make it so. And that’s what artists do.

Presence is now screening in Australian theatres.