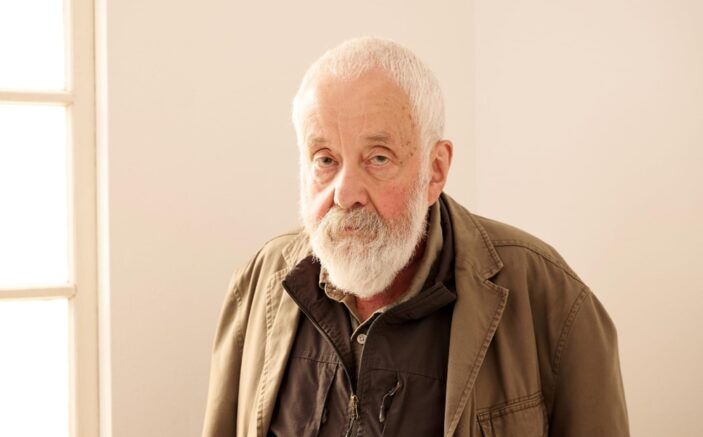

A titan of British cinema, Mike Leigh brings his signature blend of realism and emotional depth to Hard Truths, further solidifying his reputation as a chronicler of contemporary life.

Delving into the complexities of everyday existence, Hard Truths stars Marianne Jean-Baptiste as a woman tormented by anger and depression, hypersensitive to the slightest possible offence and ever ready to fly off the handle. She criticises her husband and their adult son so relentlessly that neither bothers to argue with her. She picks fights with strangers and sales clerks and enumerates the world’s countless flaws to anyone who will listen, especially her cheerful sister Chantelle, who, despite their clashing temperaments, might be the only person still capable of sympathising with her.

As the film arrives in Australian theatres (you can read our review here), our Peter Gray had the honour of speaking with the famed director about his unique improvisational method, reuniting with Jean-Baptiste, and the importance of independent cinema in a landscape of popcorn entertainment.

I was at the Toronto International Film Festival last year when Hard Truths played, and it’s always such a thrill to see films in that atmosphere.

It was great at Toronto. For a number of (reasons). First of all, I love that festival, because it’s an audience festival. You’ll agree. But also, we’d made the film the previous year and spent the first half of it having been turned down by Cannes, and then Venice, and then Telluride. It was beginning to feel that maybe we made a crap film (laughs). All of a sudden, Toronto was wildly enthusiastic, and we went there. Of course, it was an absolute blow away, and the first of a number of such experiences. Toronto was very important for us.

I can attest you did not make a crap film! It’s so bizarre to think you were being turned down, but that was ultimately Toronto’s gain. With Hard Truths, I understand that you often start your films without a script. With that improvisation method with your actors, how do you know when the character is fully formed and ready for the camera? Or is it always a work in progress?

We spend a whole bunch of time, in this case of this film, it was 14 weeks of creating the characters and exploring the back story and the relationships. During the shoot, we construct the film. We make the film up as we go along. So, to answer your question, you bring it to a head, finally, in that part of the process, and what goes in front of the camera is very precise, and that’s the stage you’re talking about. But to answer your question on a different level, you might ask the same question of anybody who paints pictures, writes novels, writes plays, writes poetry, makes music, or sculpts. How do you know? I mean, you just do, because that’s part of the creative process. And indeed, we who are in the business of putting on performances for an audience, you bring it to a head, because that’s the job. That’s what it’s all about.

When you’re talking with Marianne Jean-Baptiste, for instance, how do you handle that shift and change that comes with the move from the conversation to filming itself?

It’s a journey to the end. We embark on the journey of making the film, and through that we discover what the film is. It’s full of surprises, but that’s the nature of the creative process. How many times have you heard novelists tell you that they didn’t know what was going to happen next, but they got a message back from the world the characters they’ve created? It’s all about that, and in reference to your question, it’s about a creative collaboration with the actors. I regard the actors as creative artists, not just what they normally do, which is interpretive. It’s full of revelations and surprises, where you go “No, let’s do that,” or “I think that’s wrong.” It’s about motivation and change. But it’s all a collaboration.

You’ve worked with Marianne and Michele Austin before on Secrets & Lies. What was it about Hard Truths that you knew was the project to reunite with them?

Marianne and I stayed in touch as friends. She lives in LA and I’m in London, so there’s that, but she’s been coming and going from the UK for work for a while, and we wanted to do it. We talked about it, and we were going to do a version of this film in 2020. But then COVID put that to rest. Then it just seemed like a really good idea to get Michele in as well, because we’re a trio. We’ve worked together on a stage play before Secrets & Lies, where they played sisters, curiously enough. It just seemed like a good thing to get them together. It was just such a natural thing to do.

Going off that collaborative process, as you mentioned, does the discovery of a location influence the development of the characters within the story as well?

You create the characters and you start to think about where they would live, and so on and so forth. I make films about people, but I also make films about place. Place is very important. The mood, the spirit, the whole thing of where we live, our environment and, of course, working with good production designers. In the case of this film, it’s Suzie Davies, who has done my recent films, and indeed has just successfully been the designer of Conclave, so she’s very versatile.

In creating these two domestic locations, where Pansy lives and where Chantelle lives, collaborating with Suzie, we really wanted to create this kind of sterile environment of Pansy’s, and a more friendly, warm, plant-endowed environment where Chantelle lives with her daughters. The actual house and the locations are all very important. It’s all integrated.

One of the things I really loved are the nuances of the characters. The smallest look could mean something. Is there a conscious effort on your part to capture something that we might think is so throwaway, but then it reveals so much more? Are you looking for that? Or do you even find that in the edit?

It’s not about the edit. I mean, there is that too, of course, but both things happen, regarding your question. It happens if you really have created the characters properly and with proper foundations. In detail and organically. My job as a director, as a dramatist, as a storyteller and screenwriter, however you want to describe it, is to look for this moments and to grab things, and to make sure they’re there. When we shoot these films, we don’t do a lot of takes for all the usual reasons, like the actors can’t remember the lines or they didn’t really know the character. It’s because it’s rock solid and (the actors) know they’re very secure.

There are occasions when we’ll do the take, I’ll yet “Cut”, but I will tell them to go again. Everybody asks why because that shot seemed so fantastic, but I want to go again because in the cutting room, when we’re editing, there’ll be those subtle nuances that you’re talking about. Sometimes I will actually give a note and ask why doesn’t the actor do this or they can do the same thing again, but that’s all just in the ordinary business of film directing.

You mentioned organic portrayals, and you have this everyday setting. Is there a balance for you in finding authentic representation and adhering to the demands of dramatic storytelling? Or you find that life brings enough of its own drama?

It’s not a question of finding the balance. It’s making sure that you’re doing both things. My style of films are realism, not naturalism. Heightened realism, and that’s what you’re talking about. In terms of your question, both things are important.

It feels like we’re seeing the very real threat of the cinematic experience dissipating. Against the visual spectacle that so many people now just relate cinema to, do you believe there’s still an enduring power to character driven storytelling?

What’s harder to get made is independent films, which are films that are not interfered with and generally fucked up by the executives. That’s the main problem. Obviously, for someone like me, who says to a potential backer, “There’s no script, I can’t tell you what it’s about, we can’t discuss casting, and please don’t interfere with this when we’re making it,” I need hardly tell you that it’s tough (laughs).

I’ve made a lot of films on that basis, but it has got tough. It’s tough at this moment. I’m struggling to get a budget together at the moment, and we’ve got potentially less (money) that what we had making Hard Truths. It’s all difficult. But, the sort of cinema you mentioned, the visual spectacle, I don’t make those movies. I make films about life, about people, about reality. Yeah, the movies with the tropes and clichés that live in a hermetically sealed world separate from the world we live in, they are perfectly legitimate. There’s always been movies like that, and it will be bad news when they completely take over, but somewhere on the planet, and that means in World Cinema and not in Hollywood, people make films about life.

The truth of the matter is, we need those big blockbuster movies. All those escapist films. They are a big part of what we need. That’s what audiences need. But, of course, that’s not all they need. We still absolutely need films that reflect life and have a meaning on a level beyond a night out with a popcorn.

It can’t be stressed enough how fantastic Marianne is in this film. It truly is a shame she wasn’t more well regarded across this recent award season.

She should have got the Oscar the other day. I won’t talk about other people’s performances, but she should have been up there, absolutely.

I also want to mention the actors that played her husband and son, David Webber and Tuwaine Barret. They absolutely break your heart.

I work with character actors. That’s what it’s all about. From the young woman in the furniture store, to the guy in the carpark, to the women in line at the supermarket. The doctor and the dentist, too. All of them. And Samantha Spiro, who’s quite a distinguished actress in her own right, who plays that awful cosmetics executive, they all deliver. They all come in quite briefly and we discuss what they’re going to do, and they’re all able to improvise and do the characters.

Are you working with every single one of them individually through your process?

Always, always, always. Including even those wayward films I’ve made, like Topsy-Turvy and Mr. Turner, and Peterloo, all those characters in that climactic massacre sequence, all the actual individual actors, not the extras, I didn’t spend four years working with all the extras, but the people who play characters all went through the same process. And it’s very solid. It meant we were able to really explore those meetings with the women, and the magistrates upstairs, and those fascists looking through the window (laughs). All rounded characters.

Hard Truths is now screening in Australian theatres.