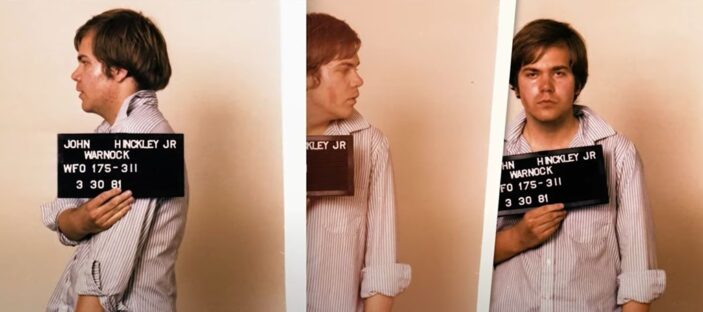

In March 1981, John Hinckley shot U.S. President Ronald Reagan in a failed assassination attempt driven by a dangerous obsession with the Martin Scorsese film Taxi Driver and actress Jodie Foster. The attack shocked the world and forever changed American history. Found not guilty by reason of insanity, John spent thirty-five years in a psychiatric hospital and now has his freedom back.

Hinckley: I Shot the President is a provocative documentary that examines the dark side of the American Dream, as Hinckley now seeks redemption through his art and music and grapples with his past in a nation deeply divided by politics and gripped by gun violence.

Bringing this fascinating examination to the screen is Queensland director Neil McGregor. After teasing this project with Peter Gray the last time they spoke for his previous film, Growing Happiness, Neil reveals all ahead of the film’s digital release, talking of its timely placement in the current political climate, the surprising openness of John himself, and the exciting journey of uncovering forgotten history.

It didn’t feel like that long ago that we had spoken, and I remember asking you about this project. Guess you got a bit more promo than you were expecting with that assassination attempt…

Look, it’s the timing of these kind of things that publicity and PR would only dream of. Obviously, the incident itself is terrible, but given the context of Hinckley and his associations I think it makes the film even more timely and relevant. But something like this was always going to have a timely relevance, and sadly in the States, there’s been a trend of political assassinations.

John Hinckley is etched in that wrong side of history with Lee Harvey Oswald and John Wilkes Booth and, more recently, Thomas Crooks, who didn’t live to tell the story of why he did what he did. So the relevance of it and the reverence for it is what was always going to be a story that just resonated. And the timing of it with an election just kind of heightened it all. If anything, it just really reminded the people that there’s so much unresolved, and this film and John Hinckley’s character holds that mirror up to that question of “Why does this keep happening?”

We see the statistics at the end of the film about the ease of buying and owning a gun in the United States, and it’s a conversation that is so often linked with mental illness. Hinckley is quite open in the film about his access to a gun and his own mental health journey. Were you surprised that he was very much an open book regarding such?

He did speak a lot more than we thought he might, and we built up quite a rapport during those conversations. I still chat with him every few weeks. That’s an earned trust for him to be able to be so vulnerable during the mention of uncomfortable things in his past. When you’re making a documentary and you step into people’s lives, you’re with them to share their story. It was certainly surprising how much he did open up and how vulnerable he allowed himself to be about both his past and his present.

We all put a guard up in any social conversation, and in many instances he let that down and allowed us to share that story. I think that was fascinating in itself, and tying back to what you were saying about mental health and the stigma around that, and the gun controls, one of the people that was injured in the assassination attempt was (James) Brady, and that spurred on “the Brady Bill”, which did a lot for background checks around mental health and the access to guns. Guns in America are kind of ingrained in the culture. It’s not as simple as an incident like we had in the 90s. (In the United States) it’s a lot more complex than that. There’s still many more steps to go.

His music is what John Hinckley loves to talk about now and have as his main focus. One of the things I found interesting in the film was that he mentions having to ask for permission to use his own name when releasing his music. Where did that originate from?

It’s a good question to ask. With his name, for him to be able to use it ties into the “Son of Sam laws.” Son of Sam (David Berkowitz) was a serial killer, and he wrote a book which he was profiting off of. Obviously you can’t profit off crime. John Hinckley, his name is etched in the wrong side of history because of the events of 1981, so in doing his music and his art, he was just requesting permission from the courts to be allowed to use his name and associate it with his art. It’s more of a formality than anything else. And, you know, his music is not to everyone’s taste, but he has a talent as a singer/songwriter, so it’s fascinating to see him move on, or try to move on, through his music.

There’s a moment in the film where we see him on the phone with an Australian media outlet to talk about his music, and he stresses how that’s what he wants to discuss. The journalist on the other end of the phone says they need to talk about his past as a way to introduce his segment. Because he’s so passionate about his music and almost seems reluctant to talk about his past, did you ever find it difficult in him agreeing to the film?

No, not at all. When we first started talking about doing a documentary, you sort out the general parameters of what you’re going to do, what you’re going to talk about, how you’re going to approach it in order to separate the art from the artist, which is a very common conversation now. And I think even more complex and challenging with someone like John Hinckley doing music and then looking at his past. You see that in that interview, as you said Peter, where he talks to an Australian journalist, and he’s done the same thing to every journalist around the world – Japan, the UK, the US – where everyone wants to talk about his past, but there is an interest in what he’s doing now.

That, for me, was what attracted me to this project. How does someone do that and go on with their life? Making music is such a fascinating transition. His past is such a tricky thing to shake, so it was really challenging for him to be able to move on, and journalists obviously always want to talk about his past. But, for us, with the film you see the understanding as to who he is as an artist and as a person. But you can’t do that without (acknowledging) their past. That’s the journey that got them there. That’s a creative pathway.

But with someone like John Hinckley, it’s part of his story. There’s some uncomfortable truths in the past, you know? We’ve all made mistakes. Perhaps not as big as something like we did in a poor state of mental health at the time, but it’s important to make sure that we (addressed) that in the right way. We couldn’t excuse the actions of the past.

Did you find that in discussing his past, he addressed it as if it was a different person entirely? He’s so matter of fact about it. Was there a disconnect you noticed in how he talks about that time?

A little bit. I mean, you’ll see this with anyone that has gone through a very traumatic event, they’ll find a way to deal with it in their own way. And a common way to deal with traumatic events is that you’ll deal with it, but not dwell on it. Interestingly, the way he talks about his past and those events is similar to how Jodie Foster speaks to those events. And she’s as much of an indirect victim in all of this too.

When you’re interviewing John, and he’s telling you about being pen pals with Ted Bundy and waiting outside the Hilton Hotel to shoot the president, he tells that his only concern was where he was going to get his next Valium hit on the way to a record store. He’s this very normal person having a conversation, and it’s interesting to see those uncomfortable requirements for him to be able to keep recalling these traumatic events of his life. We’ve seen it more recently with the Trump incident, which brought up a plethora of very uncomfortable emotions for John, who had battled severe mental health issues. And what you’re seeing there is the person he was and the person he is.

How difficult a process is it to garner the FBI footage? And then from that, the voice notes he has from Jodie Foster? Is there a process in getting any permission for such?

It’s a very complex challenge. It’s a great one (though), because you find things that people hadn’t seen before or, in this instance, we found photographs and videotapes that had to be digitised because they’d been sitting on a shelf for the last 30, 40 years. It’s a fun adventure into the unknown. You don’t know if some of the stuff you’re looking for exists. We had a fantastic amount of support from Getty Images Australia, so they helped us dig through some archives, and the Reagan Library was very supportive of the project and helped us find some things. It’s always an enjoyable process, but it’s challenging because you find things that are so in depth, as well as things you don’t expect to find, or that you didn’t know were out there. Then you ask yourself, “Should I include this in the edit? Or is there something more we need to explore?” You have to pick and choose the best stuff, and not everything makes the final edit.

And with Jodie Foster, obviously John had recorded that. He went to see Taxi Driver on a whim, and he was battling mental health issues at the time, and Travis Bickle, the particular character that Robert De Niro played, is a very similar kind of character to “Catcher in the Rye”, which was a whole other part of a conversation in itself. But here is someone in their 20s, isolated, and they found it easy to connect to that particular character. I mean that’s the amazingness of what Taxi Driver is. Cinema has the power to change people’s lives, for better or worse, and in this instance, for John, he just became so obsessed with Jodie Foster, and that blurred the lines of separating the fiction of the story versus the reality of an actress playing a character. That really just goes to show how unwell and how poor his state of mind was. He just couldn’t get that fixation out of his mind.

It’s a very unfortunate thing for Jodie Foster that she was an indirect victim of all of these circumstances outside of her control. I know she rarely speaks about it. During our archival search, there wasn’t much out there (about) it. She’s definitely someone who was impacted just as much as any of the four people that John Hinckley shot in 1981, and he even says in the film that in hindsight, with a clearer state of mind, that there are more steady fields for dragging someone into it.

And now releasing his music, I know it was encouraged as a form of therapy. Did he ever speak about an artist or a song that truly inspired him?

Music’s always been a huge part of his life. In some ways, it was an undercurrent that he lost to his mental health. He always adored Bob Dylan. That was certainly someone that he admired. John Lennon was also someone that he absolutely idolised from a young child, seeing The Beatles in the 60s on The Ed Sullivan Show changed his life completely towards the direction of music.

Through his art and music therapy, he was able to refine some of those inspirations that he’s had. He’s always loved that folksy, 60s sound, and that’s the type of music he plays and writes. He’s a very talented singer/songwriter. You think how different his life might have been had his mental health been checked and understood, and what path he could’ve been put on. It’s fascinating that he idolised John Lennon so much (too). When Mark Chapman shot John Lennon in 1980, John was going through the depths of his illness at that time, and it was what really put him over the edge of looking into the attack on Ronald Reagan outside the Hilton Hotel. It’s a really fascinating thing that music has been so entwined in his life, and now in his late 60s, he’s trying to pick up where he left off and embark on a music career.

Hinckley: I Shot the President premieres August 30th on the platform Launchpad. For early access from August 27th and for more information on how to pre-order the film, head to the official website here.